https://www.art-it.asia/en/top_e/admin_ed_feature_e/203677

MINOUK LIM

SEEING THE SOUNDS

By Andrew Maerkle

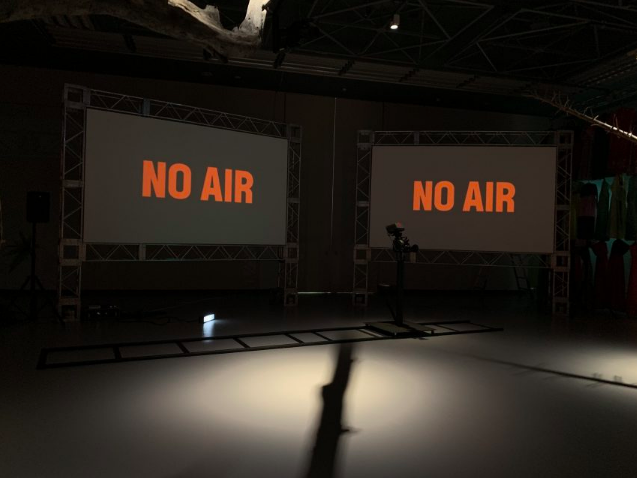

Adieu News (2019), mixed-media video installation, dimensions variable, 13 min 35 sec looped, installation view, Aichi Triennale 2019. All images: Unless otherwise noted, courtesy Minouk Lim and Tina Kim Gallery, New York.

Born in Daejon, South Korea, in 1968, Minouk Lim turns a playful yet critical eye onto the underside of the contemporary Korean folk consciousness and the repressive structures that shape and mediate it. Her videos, performances, installations and interventions into public space reveal the hidden continuities extending between Japanese colonial rule and the present; or between suppressed memories of civilian massacres in the years surrounding the Korean War, when thousands of suspected communist sympathizers were killed in purges and other reprisals, and the veneration of the new demanded by global neoliberal consumer culture; or indeed between the inverted mirror images of authoritarian regimes in North Korea and predemocracy South Korea.

In recent years, Lim has focused on how the mass media serves as a contested terrain between people and power, as in The Possibility of the Half (2012), which juxtaposes footage of mourners observing the deaths of South Korea’s Park Chung-hee and North Korea’s Kim Jong-il, respectively. Similarly, her solo exhibition in 2015 at Seoul’s Plateau, Samsung Museum of Art, “The Promise of If,” was inspired by the South Korean national broadcaster KBS’s special program Finding Dispersed Families, which aired in 1983. What started out as a one-off program to help reunite family members who were separated some 30 years prior in the chaos of the Korean War ended up airing for more than 435 hours over 138 days from June 30 to November 14, 1983, and featured more than 53,000 participants. Lim has since used the footage and iconography from the program as sources for multiple works, including a large-scale installation she presented at the Busan Biennale 2018, “Divided We Stand.”

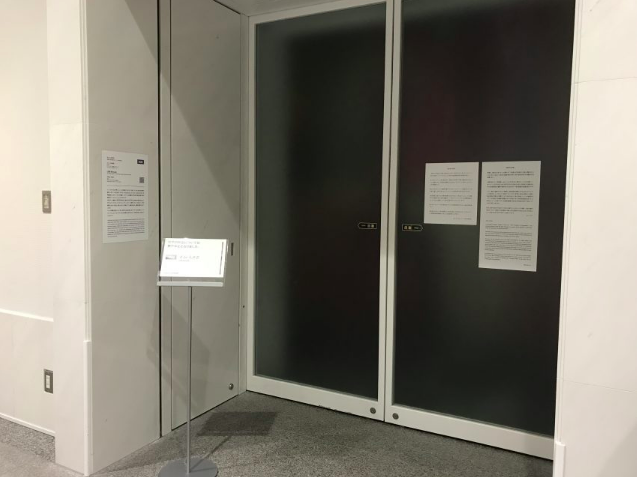

The following text is based on an interview that was conducted in English with Lim in Busan in September 2018 on the occasion of her participation in the Busan Biennale. Over the past year the transcript went through multiple stages of editing, translation into Korean, retranslation into English, collaborative editing and further revising. In the middle of this process Lim was embroiled in controversy when she decided to withdraw her work from exhibition at the Aichi Triennale 2019 in protest over the closure of one of the sections of the Triennale, “After ‘Freedom of Expression?’”, just three days after the August 1 opening. She and another participant from South Korea, Park Chan-kyong, were the first artists to withdraw their works, effective August 6. As of this writing they have been joined by 13 other international and Japanese participants who have either temporarily withdrawn, completely withdrawn, or altered their works in solidarity with the closed section. On September 30 it was announced that the organizers of “After ‘Freedom of Expression?'” had reached an agreement in court with the Triennale to reopen the section before the event concludes on October 14.

The Busan Biennale 2018, “Divided We Stand,” was held from September 8 to November 11, 2018. The Aichi Triennale 2019, “Taming Y/Our Passion,” opened to the public on August 1 of this year and continues through October 14.

Interview:

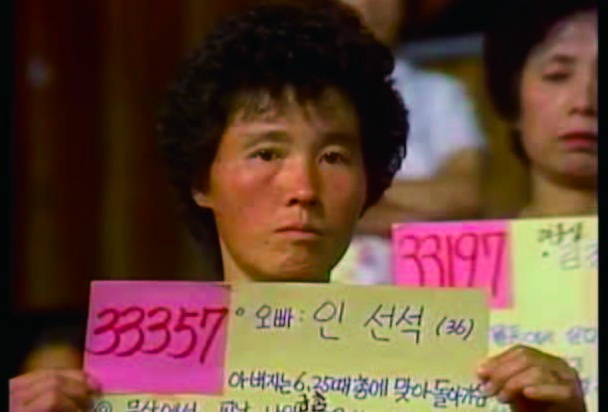

The Promise of If (2015), still image from two-channel video projection, 30 min. Video courtesy KBS.

ART iT: Your career spans several phases, starting with the collective projects you did in France at the beginning of the Relational Aesthetics era, followed by your move back to South Korea and your turn to looking at events in Korean history—particularly those that relate to the Korean War. One theme that seems to run through all these phases is a continued interest in singing, poetry and music, as seen in works ranging from New Town Ghost (2005), which involves a musical performance on the back of a truck driving through Seoul, to O Tannenbaum (2017), which traces the history of the titular German folk song. Where does that interest come from?

Minouk Lim: I think I’m a failed poet. But song and music motivate me to create new works. They give me the courage to push myself beyond boundaries. Music was always in the background of my childhood years. My sister played the piano, and my grandmother’s Buddhist chants sounded like lyrical tunes to me. I went to a middle and high school founded by the Unification Church, so during those years I used to sing in the choir and attend classical music performances. After I moved to Paris, music became my safe haven. It transported me back home in an instant. I think it was around this time that I got interested in the idea of the territories that could be created by music and its performative aspects.

After my return to Korea in the late 1990s, I became friends with a group of underground musicians. Pioneering Korea’s early techno music scene with them was a particularly memorable experience for me. The environment was very intersectional and felt different from the art world. It was like having the power to create communities, but be free from them at the same time. Since then, I have been fascinated by music that possesses the same kind of shamanistic power—the kind of music that can break apart and rearrange its original form, and be passed onto others without a score.

But these experiences have helped me to understand that although we like to think music has no ideology, that it is universal and brings people together, it can also be a powerful tool for ideology.

ART iT: A challenge of working with both music and ideology in visual art is that, in a sense, neither of them offer anything to see. We can easily make the mistake of assuming they are immaterial, when in fact they have strong material effects.

ML: When I listen to music, I always feel as though I’m scanning its texture. It’s kind of like 3-D printing the music through my ears in reverse. Music is not immaterial, but it is molecularized based on territory, as with bird calls. It makes boundaries and is in turn made by the boundaries, which I see as a kind of self-collapse. This point of self-collapse is what interests me: where one needs the other but cannot be differentiated from the other at the same time. In this way, music is a machine, an animal, a god and a weapon. (This suddenly makes me think of Woody Allen’s joke about how listening to Wagner’s music gives him the urge to invade Poland.)

In a materialistic society, ideology endlessly disguises itself in different forms and positions, and so it is hard to discuss the end of ideology since it is impossible to define what is dominant in the first place. Behind a cup of coffee, a bowl of ramen noodles, or behind the street corners and the horizon, all kinds of ideologies—the ideology of the everyday, the ideology of innocence, the ideology of peace and security, the ideology of change, the ideology of hope—create endless fantasies. I am no different. Tomorrow, we will continue to build our invisible altar piled with the newest “it” items, pets and selfies, while politicians and experts will meticulously observe and analyze the phenomena on which they continue to build their authority. I will try to confront them and rearrange the order, and then the cycle goes on.

Both: New Town Ghost (2005), still image from single-channel video projection with sound, 10 min 59 sec.

ART iT: In New Town Ghost, a woman raps about a consumer-driven society where, with a little money, anything from one’s complexion to whole communities can be cosmetically altered and improved, but appearances might not be as they seem. What got you interested in the theme of Korea’s modernization?

ML: I went abroad to be free, to be educated and to experience a new world. But in the end I returned home. Naturally I began to question what change really means, and what it means to dream. I found myself caught up in desire and despair at the same time. Even after 13 years away, I was once again faced with the endless cycle of Korea’s nostalgia for dictatorship, state-led modernization and anti-communist propaganda. The idea of community in Korean society was fundamentally fractured by Japanese colonial rule and then further divided by dictatorship and overnight modernization. Yet it never broke down to the level of “individuality.” I was told that since I was fortunate enough to study abroad with my parents’ support, I should stop criticizing Korean politics and focus on working hard and being successful. But there was still so much I didn’t know. I wanted to keep learning. I felt I should reeducate myself on what modernization really means. I had to reexamine when and how it began, and where it was headed. At the same time, these questions stemmed more from observations of my everyday life and environment than academic interest.

ART iT: Do you feel a sense of conflict in having benefitted from an economic system that extends from the authoritarian structure of the dictatorships of Park Chung-hee and his successor Chun Doo-hwan?

ML: I was born in the 1960s, went to college in the 1980s and left for Paris in 1988.

The former Japanese prime minister Shigeru Yoshida once described the Korean War as a blessing for Japan. But instead of asking for an apology for invading our country, Park Chung-hee took out loans that he used to develop Korea’s economy in the 1960s. Following Park’s assassination in 1979, the 1980s were the era of Chun Doo-hwan, who seized power through a military coup. It was a time of censorship and torture, but unprecedented economic boom. In 1987, when other college students were rallying against the authorities in demand for democracy, I made my daily commute to and from my studio in Shinchon with canvas in hand. When other students were being tortured by the authorities, being struck with tear gas and losing their lives for the cause, I read Baudelaire and Camus, and did nothing. I was in my junior year of college at the time. I was once asked to write a letter of apology after commenting at a critique session that a painting of a flower looked like an illustration. Shortly after, I went to Paris without finishing my undergraduate program. That was the year of the Seoul Olympics, and I became one of the first to benefit from the government’s lifting of the overseas travel ban for Korean citizens. I still stand like a ghost in the midst of all this history.

Both: Navigation ID (2014), installation and performance view, opening day of the 10th Gwangju Biennale, “Burning Down the House,” 2014.

ART iT: You’ve revisited the issues that you address in New Town Ghost throughout your career. Concurrently, you’ve made a series of works about civilian massacres that took place during the Korean War, as in your project for the Gwangju Biennale in 2014, Navigation ID, for which you transported shipping containers holding the remains of massacre victims to the square in front of the Biennale Exhibition Hall. Do you see a connection between the phenomena of nostalgia for the dictatorship and amnesia toward the war period in contemporary society?

ML: My works stem from narratives I had originally set aside because they were too “personal,” but then tried to come to terms with because they reflected the conflicts and crises that my family and I had faced over the years. They are about memories, secrets and fear. At the same time, they do not only concern the past. They also deal with the open wounds that remain in the present.

My parents were survivors of the Korean War, and their lives were forever haunted by traumatic memories of their experiences. As I delved deeper and deeper into their memories of the past, I had to know more about the history. Yet my father saw this desire as a challenge against him. He did not tolerate any criticism of the history of dictatorship. Instead, he chose to voluntarily erase his memory. When asked about the civilian massacres that occurred in his village during the Korean War, he simply responded that we should “know not to know.” My understanding is that he was ashamed about what happened and his amnesia was a way of protecting his dignity. My father insisted that we should keep striving for a better future, but ironically his nostalgia for the dictatorship and voluntary memory loss trapped him in the past for life.

ART iT: Of course Japan is another country where a rigid patriarchal structure often impedes the processing of historical traumas.

ML: I think it is even more so under the current Abe administration. We all know who Abe’s grandfather is. Nobusuke Kishi was jailed as a suspected war criminal. It seems Abe wants to revert back to the imperial glory of his grandfather’s era. Today’s Japan was built on the absolution and support of the US government in exchange for collaborating on the anti-communist front after the Korean War. It is time that Japan stops blaming the victim and faces the past. Regression happens when history is distorted and memory selectively edited. And what could be worse regression than when there is only hate left to be passed on to future generations? In this context, Japan’s Kishi, the so-called “ghoul of Showa” (Showa no yokai) whose powerful influence lasted long after his death, and Korea’s Park Chung-hee are eerily like twins. The supporters of Park Chung-hee’s daughter and former Korean president Park Geun-hye in Korea and the supporters of Abe in Japan are destroying our hopes for peace.

It’s like the image of self-collapse I mentioned earlier with regard to music. My father could sing “Kimigayo,” just like Park Chung-hee. I remember he would sing it secretly to himself. There are also fragmentary memories of a Japanese sword and shrine being in our home. I don’t know what they were for exactly, but one day they just disappeared. It’s an enigma to me.

In contrast, when I was researching the civilian massacres of the Korean War, my mother talked for the first time about her memories. She recalled how young the North Korean soldiers were—only 15 or 16 years old—and said they taught her songs under a tree. It struck me as a really beautiful image. But she said the war was horrible and cruel. One day she came across a group of American soldiers who were swimming naked in a river. The next moment they were all killed by a North Korean sniper hiding in the mountains nearby. That was something she witnessed. Even long afterwards she was very sensitive to sudden bursts of noise.

These stories only came out very late, so I didn’t have enough time to talk with my parents about them. They always took me for a commie, a North Korean sympathizer, and not someone to be told such things.

ART iT: When were your parents born?

ML: They were both born in the 1930s. My father’s experience was deeply rooted in the colonial past. He attended primary school under Japanese rule and learned to speak Japanese. But he came from difficult circumstances and struggled to survive, let alone get an education. Just before the Korean War he voluntarily enlisted in the military to escape poverty, and so to him the government was his life saver.

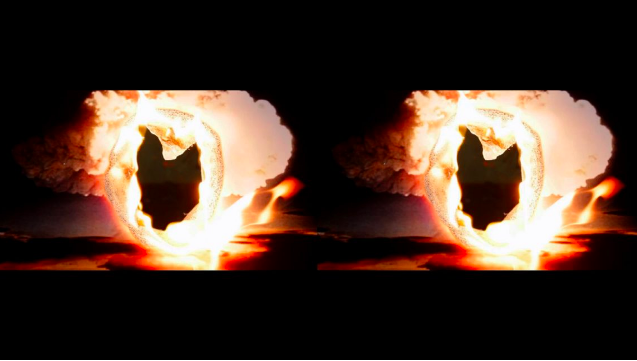

Both: The Possibility of the Half (2012), two-channel synchronized projection, 13 min 23 sec.

ART iT: There are probably many men in Korea from your father’s generation with similar stories.

ML: Yes, my father could be the prototype. Politicians in Korea used to say that you should hop in a cab to gauge the public sentiment. But this is a bad idea if we really think about it in the democratic sense, because taxi drivers mostly just repeat the same agenda over and over again. The drivers always talked about the hard times we had to endure to rebuild the country after the war, and how if anyone wants to protest against Park Chung-hee or Chun Doo-hwan they should be sent to North Korea. But hate politics and closed-door policies work the same way around the world, whether in Korea or Japan or the US. If anyone is different from what we are, they are marked as a threat and excluded by exploiting the ideology of security. Years ago, when the “anti–Roh Moo-hyun” sentiment was at its peak, seemingly every taxi driver I met would talk about their nostalgia for the “miracle of the Han River.” I tried to capture their sentiment in my video installation Wrong Question (2006). My methodology is to create a work when I want to put an end to something that seems to be endless.

ART iT: Surely one reason these men are prototypes must be the purges that occurred throughout the war period.

ML: Right. It’s a survival mechanism and the reason why they see everything as a war. It’s the logic that all competitors must be eliminated in order to survive. I used to think this kind of logic was the legacy of Japanese colonialism, but it seems to lie at the core of the neoliberalism that dominates the world order today. At the same time, the reason why the war metaphor persists in Korea is because we still remain a divided country. Would it really have been possible for the anti-Japanese resistance and the pro-Japanese collaborators to suddenly shake hands and come to a truce after the liberation? There was no choice for them but to either seek revenge or betray one another. After the US and Soviet Union divided the Korean Peninsula for military convenience, the country was once again torn by ideology and plagued by the mentality of “kill or be killed.” It is against this history of bloody purges that Korea’s first president Syngman Rhee came to power, followed by Park Chung-hee. This is also why the endless controversies over the distortion of history continue to this day. The situation is no different in Japan.

ART iT: Would you say then that Navigation ID and the The Promise of If (2015-18), which deals with the Korean national broadcaster KBS’s special live broadcast from 1983, Finding Dispersed Families, are interlocking projects?

ML: There were three live broadcast events that were particularly memorable in my life, all of which reminded me how politics and art share the same roots, in that they cannot be controlled by logic or reason. First was the state funeral of Park-Chung-hee in 1979. Second was 1983’s Finding Dispersed Families, and third was Nam June Paik’s satellite broadcast Good Morning, Mr. Orwell in 1984. In 2012, I cross-edited scenes from Park Chung-hee’s funeral with those from the 2011 funeral of North Korean leader Kim Jong-il for The Possibility of the Half, the first video installation in which I presented the broadcasting studio as a site of ruin. The work centered on the impossible gaze, and my subsequent works Navigation ID and The Promise of If all relate to one another in this aspect.

Both: Navigation ID (2014).

ART iT: My initial concern with Navigation ID was that its use of broadcast and livestreaming media, along with the helicopter and ambulance escort for the shipping containers as they were being transported, might spectacularize grief. But now it seems the work could only make sense if done on a massive scale.

ML: I wanted to make it spectacular because I thought that technology should serve the unseen, unspoken, erased things in our societies. Considering that most media outlets self-censored the “spectacle” themselves, perhaps it was not such a successful spectacle after all.

Nam June Paik’s Good Morning, Mr. Orwell demonstrated how cutting-edge media technology can facilitate peace and communication for humanity. It was a cheeky homage to George Orwell, who warned against mass media’s controlling influence over us. In 2014, I in turn created a cheeky homage to Paik when I livestreamed the procession of containers with the abandoned remains traveling on the road. I wanted the work to show how the world today, which is more connected than ever by the internet, does not coexist in harmony and peace, but has become a world of hate and discrimination. Even in death, we are divided by ideology, and denied proper funerals. George Orwell was all too right in his prediction. I wanted to question whether the livestream could make up for the funeral. People part and reunite differently in the realm of frequencies.

ART iT: Does that relate to why you call the work in Busan Promise of If?

ML: You can speculate two different meanings from the title. One is that there is no such thing as chance, and the other is that there is only chance. The people who appeared in Finding Dispersed Families seemed to me to be casting dice through the broadcast. They wanted to keep the possibility open for someone to take the place of their lost family members, and it almost didn’t matter who. They were so young when they were separated they could not even remember their name or age in some cases. There were so many question marks in their self-descriptions. But this uncertainty is precisely what the national broadcast tried to eliminate and keep under control. Thus I believe the dispersed families adopted “if” as an alternative strategy for making the meaning of evidence null and void.

ART iT: I felt strong tensions between restraint and excess in the Promise of If. The central installation with all the camera equipment and the big circular light hovering over the space suggests some kind of apparatus of inspection and control, whereas the people speaking in the video projection express powerful, uncontrollable emotions.

There are also strange details that emerge from the testimonies—repressed memories that emerge as if by accident. One woman mentions that she used to be called by the Japanese name Katsuko, while another man says he has scars on both sides of his neck, and another remembers that there used to be juniper trees near his family home. Only given a minute or so to appear on air, the speakers have to submit to a rigid format of speaking, yet in the excesses that escape that format their testimonies take on a poetic quality. Then the TV announcer interrupts them to move on to the next person.

ML: The objects used in the installation were based on the mannequins or substitute models that the dispersed family members left at the television studio to hold their places in case their relatives showed up to look for them when they were not around. The video was edited based on the understanding that memory is all the evidence the family members had to prove their identities. At the same time, their memories had become scars that were only faintly visible after many years, or recollections of objects and landscapes that could belong to anyone and anywhere. The most important part of the video is the question marks the families wrote for themselves on their self-identifying placards. They are the faces left blank to open possibilities. I know they cannot lead to anything, but they are the spaces in between, like parentheses, or the hours of dusk and dawn when we don’t know dog from wolf. Their testimonies can neither be analyzed nor proved, but continue to slide out of grasp.

Above: The Promise of If (2015-18), installation view at Busan Biennale 2018. Below: Detail. Photo ART iT.

ART iT: Right. When we see the footage of long-lost family members reconnecting through the broadcast, it actually looks staged—which it is to an extent, of course.

ML: For people to confess that they came from North Korea after the war or that they still had family there was like coming out with a secret that made them vulnerable to discrimination and exclusion, simply because of guilt by association. Many North Koreans who moved south after the war hid their personal history or became far-right conservative leaders of the anti-communism movement. This is why some placards show pictures of the Korean taegeuk flag, or unnecessary slogans like “Thank you, KBS” or “Bring down communism.” But in reality, many of the missing family members turned out to be living in South Korea, so the moment of reunion probably felt like a huge release of pent-up anxiety for them.

Therefore it is impossible to assume or define anything in these situations. No one can say they understand the sorrow of others. At the same time, we can’t help feeling sad and tearing up when we witness a moment of reunion or hear the uncertain recollections of the reunited relatives. Why do we feel this way? Because we are naïve? Incapable? Deceived? Still we cannot fight the tears. Perhaps the reason why I continue to study the footage is because I still don’t know the answer to these questions.

ART iT: The work identifies the intersections between human emotional tragedies and the deployment of state ideology and power?

ML: I see it more as their failure to intersect. There is no doubt that the state must be held accountable for the systematic violence that occurred, but more than documenting the facts, I wanted to focus on highlighting what is vanished and absent from the footage. In this country where nothing lasts forever, I wanted to question the witnessing power of human vision while examining the intersections of death in life and life in death.

ART iT: The longing for and uncertainty over individual family reunions is of course a metaphor for the possibility of an eventual North–South reunion. In fact, it is the ultimate metaphor for North–South relations.

ML: After the Korean War, the country lapsed into a void where we were completely unaware of each other, and we continue living in that void. Though merely a two-hour drive away, the other side is like a black hole to us. Both sides are fixed only on the here and now without any regard for what comes next. I think the metaphor of family in my works relates to issues of not knowing who we really are or not knowing where we come from. I always want to point out these gaps in our awareness. I want to ask viewers: Are you sure you know who you are?

View outside Minouk Lim’s display area at Aichi Triennale 2019, photographed August 6, 2019. Photo courtesy Minouk Lim.

ART iT: We started talking about music and sound as a kind of invisible material. Perhaps we could think of the “if” as another invisible material. You can make an installation that shows the possibility of “if,” but never the actual “if”—because there is never an actual “if.”

ML: The installation is like a conduit. We are never able to occupy the same place that it describes.

ART iT: Do you think your installations are empty, in that sense?

ML: I genuinely believe that my work opens up a different world somewhere by simultaneously performing the roles of environment, territory and stage. It has to be an empty space to allow communities of others to form there. I guess that’s why I don’t want to make my installations too simple or straightforward. I want to make viewers feel lost, so that they can recognize the emptiness.