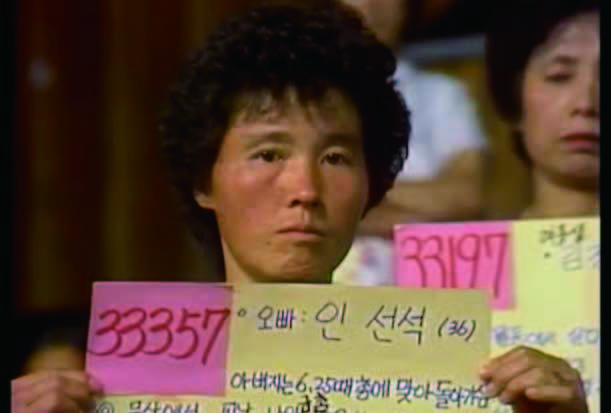

Still image from The Promise of If 2015

Video projection of 1983 KBS live broadcast “Finding Dispersed Families” reedition in loop.

30min.

Minouk Lim – The Portrait of a Dispersed Community

Interview/ Art World Magazine

Jungwon Park, Chief editor

“Look how I forget you. Look how I have forgotten you. I desire to have no more country. I will teach my children malice and indifference, and the love of other people’s countries.”

From Hiroshima Mon Amour by Marguerite Duras

In crowded downtown Seoul, the 1983 KBS (Korea Broadcasting System) live broadcast “Finding Dispersed Families” is being screened under a new title, The Promise of If. The faces of the dispersed family members, who candidly entrust themselves to the media in desperate longing, are zoomed in and replayed in slow motion, imbuing a sense of pace that allows for remembrance. The footage, made possible in this only divided country in the world, is now enlisted on the UNESCO Memory of the World Register. The following article on Minouk Lim’s exhibition The Promise of If (12.3.2015 – 2.14.2016) at PLATEAU, Samsung Museum of Art is based on the editor’s interview with Lim on December 9 and the artist’s forum presentation “Disappearance and Dispersion” at the Junglim Foundation on December 15, 2015. The interview questions follow the order of artworks as presented at PLATEAU.

#Division

The current exhibition, The Promise of If, takes its motif from the 1983 KBS live broadcast “Finding Dispersed Families.” When did you begin to take interest in the division of Korea as a subject?

I was interested in looking at vanished places and dispersed communities in the rapid process of modernization, more so than the subject of the division. Our sense of time and space dramatically altered by the experiences of modernization was something I could not avoid questioning like everyone else. It was somehow related to integration of my character within the contexts surrounding me. From the relationships from my childhood, I arrived at the underlying issues triggered by the Korean War and division, encountered by a sense of fear that something is lacking or omitted. But beyond the division, it was more about the discordance and alienation, as well as the dichotomous mindset of our society. My parents, and the Korean society, provided me the opportunity of so-called advanced global education, but when it comes to political ideology, my thoughts were inevitably hindered by the same dichotomous mindset. Not allowing any room for thought, the rapid pace of modernization instead divided our way of thinking into antagonization. It was through this context that I arrived at the subject of the division.

As in the ambivalent title of the exhibition, The Promise of If, it was difficult to draw out any single coherent meaning from the exhibition. Its clues seemed to be scattered all over, much like a fragmented portrait reflecting our current state of division.

I think being itself is rupture, if nothing else. My works are a kind of mutants from displacement. If the works in this exhibition feel like a scattered portrait, I would like to think that it is because they convey moments from my personal experience while walking, driving or even dreaming, to the viewer’s mind. I would hope that it creates a moment that mutually allows the viewers to rediscover their forgotten memories and a renewed sense of affinity. Also, in the past and even now, my works are not documentary in the conventional sense. It is more cross current in the rearrangement. In my own way, I tried to reveal the things that are entangled, hidden and blocked, before breaking things apart into judgements. The essence of all things is ultimately intertwined, and to acknowledge or to think about this is extremely difficult. It is much like being lost in a city. In this sense, one could say the fragmented portrait is more realist than surrealist.

# Containers

The first work at the entrance of the exhibition is The Gates of Citizens, made from discarded shipping containers. Your 2014 work Navigation ID, presented at the opening of the Gwangju Biennale, transported containers filled with remains of the civilian massacre victims from Gyeongsan and Jinju to the exhibition site. Merged with the theme of death, the objects must have felt even more massive. Please elaborate your thoughts on these “containers.”

This exhibition, The Promise of If, looks at between the lines of “disappearance” and “dispersion.” The same could be said of my earlier works, as they attempted to question and examine the realms of the individual and community by continuously searching for things that are lost. With projects like Jump Cut (2008), New Town Ghost (2005), and LOST? (2004), I tried to think about those that have been lost, left out and overlooked in the rapid process of modernization, and also to contemplate the relationship between our sense of speed (of the times) and memory. It was during my research on the National Guidance Alliance (also known as Bodo League) cases that I had the chance to look through the archives of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, through which I discovered the containers in Gyeongsan and Jinju. In my search for the dispersed communities, I kept seeing the containers everywhere. Since then, the questions on modernization began to linger on over the time gap between disappearance and death. It ultimately led to questioning when and who determines a person’s disappearance, and when and how that missing person could be reported dead. More questions followed on what defines a nation and what it is. As I began asking those questions, I witnessed the live news broadcast on the sinking of Sewol, the passenger ferry capsized by overloaded containers. The dead bodies recovered from the sea were sorted into containers, while the memorial altars and temporary housing for the families of the victims were also set up in containers. I was simply asking why it is the way it is, as I transported those abandoned containers from Gyeongsan and Jinju to Gwangju. The containers as one of the greatest innovations of modernity, and those containers filled with human remains – how could they have reconciled in such a way?

The rounded hallway from The Gates of Citizens into “Gallery A” is also built with containers. What is the meaning behind the title of this space, The Cave?

I used the container sections cut out from The Gates of the Citizens and used them to wrap around the round wall like wings. The Cave is a kind of self-made tomb that houses my earlier works. A tomb is a place that cannot be conquered. Containers are usually considered as common objects in our daily lives, but here, they are overlapped with death. In this setting, the containers create another kind of place that connects the communities united by sorrow, as with the container “caves” that held the remains of the civilian massacre victims.

# Media

In the back section of the exhibition is the video work, The Promise of If, edited from the 1983 KBS live broadcast “Finding Dispersed Families.” What are your views on the media?

I started to obsess over the question of what defines a nation, as I looked deeper into the sites and testimonies of the National Guidance Alliance cases. And from this, I became interested in the format of newsrooms and began making sculptural objects of media devices in half human and half organic form. At the same time, I wanted to question how the dichotomous mindset of our divided country, which ironically made a significant contribution to the modernization of Korea, is reflected in the media. It was at the time that I came up with the concept of a broadcasting studio that serves as a meeting place.

A broadcasting studio seized by the dispersed families – it marked a historic moment and a new kind of media operating on a different spectrum of emotions. However, as the days went on, the KBS broadcast eventually reverted back to the existing system and ideology of the time. During my research, I visited the on-site reenactment of “Finding Dispersed Families,” publicizing its submission to the UNESCO register. The event was taking history as its object of representation. The installation of mannequins holding replicated storyboards and the reenactment of the live coverage by an actor imitating Kim Dong-gun (original host of the live broadcast) seemed completely surreal to me beyond words.

So, I decided to reimagine a surrealist broadcasting studio seized by the dispersed communities. I focused on how the media created by the participants’ desperate longing began to occupy space in a different order. The KBS live broadcast, therefore, became a kind of pivot joint. The Promise of If, started as a kind of imaginary broadcasting studio that calls on past memories, in search of those lost ones between disappearance and dispersion. Could we open up new possibilities at the edge of the sorrow consumed by ideologies? This is my question and attitude towards the media.

# Art

The last room of the exhibition presents the installation, Running on Empty, which looks like a hidden studio in preparation for a live broadcast. The various sculptural objects made with materials such as buoys, feathers, faux fur, algae, sea shells and fishing nets convey delicate yet strong subjectivity at once.

The materials were selected upon picturing a scene of catastrophe, and at the same time, a cave of modernity. I thought about objects on the edge of another dimension, and their salvation. For example, in the movie Pirates of the Caribbean, there was a scene where the world is turned completely upside down, and it inspired a certain image for me. It was an exhibition space as a docking place for return. Return of the disappeared. In that imaginative space is the site of media that speaks for the overlooked, forgotten and excluded. So, the installation entitled, Running on Empty consists of a series of sculptural objects, which I imagined would come to life at night and roam free in their own memories. I would hope that these aspects would deliver a sense of subjectivity and vulnerability in the relationship of the objects.

The viewers of the exhibition are inevitably faced with the uncomfortable truth. What significance does the exhibition space have for you?

The exhibition space is not a salon decked with comfortable furniture. It is neither a place to search for right answers. The act of exhibiting artworks puts the viewers in performance with the works, and in that space creates disharmony through their relationship. It demands that our perspectives be continuously reexamined. Before the current age of spectacles, the act of “seeing” was probably very different, and so I think the exhibition space today stands between the lines of performance and documentary where the objects and archives seek the invisible.

When entering the exhibition, I assumed that The Gates of Citizens symbolized hopeful messages of reunification and peace. But after our conversation, I think the work reflects on the times that we must not forget and encourages new perspectives on those times to be remembered.

Upon entering the exhibition, you can hear the soundtrack accompanying the work that plays everything from pop music to movie soundtracks. Between the tunes, you can even hear voice recordings of the truck driver who transported the containers of the human remains. This soundtrack bridges both time and space inside and outside of the museum. I wondered if one could challenge an installation artwork to become a kind of live broadcast; a broadcasting studio transmitting and receiving the stories and recovering the wishes of dispersed communities, just as the live broadcast of “Finding Dispersed Families” once did. The duality of time and space created in that moment was what inspired The Promise of If.

Translation Nayoung Jo