Art Talk_Minouk Lim : Taking a Pause-A Methodology to 'Confront' Intangible Objects

One can find a number of sentiments combined in Minouk Lim's works: resentment, anger, passion and remorse. The artist, positioned at the forefront of those who believe that modern confrontation between politics and art no longer exists, effortlessly expresses his complex but unique sentiments that appear on the hidden side of the language of resistance. It is clear that Lim went to great pains not to regard the object as an enemy; this became evident when she pointedly commented on the reality of our society ‒ the remnants of whose compressed growth are still creating chaos. In light of such a reality, we can only feel hopeful to discover the maze that we live in ‒ if we could only trace back the path that Lim is wandering on.

The Weight of Hands, HD video & sound, single channel projection, 13'57", 2010

© Minouk Lim

Koh: Your video work is mixed with complex elements such as sentences (writing, language), performances (theatrical), videos, installations, etc. These elements, coupled with a given space of time, remind us of making a movie. Your work can be viewed as a kind of movie. What is your take on this?

Lim: My motivation for work started when I was faced with a so-called 'Movie-like' reality. On the hidden side of this preposterous encounter, there were stories that embraced the story behind the truth, putting it in greater context. In a world that requires us to have logical thoughts, looking into the suffering of history ‒ where irrational events take place ‒ can help us better understand where the paradoxical relation resides.

I believe that art and movies can be the media that can arrange for this 'encounter.' However, for the movies that have restrictions in the production area, 'The censorship within' is activated from the inception phase. Moreover, art is a language that raises questions, not being a hostage to any form of censorship. From the perspective that it is possible to be self-reflective, we can give some credit to the fundamentals of art. I like this unique feature of art that rules out censorship and ranks. The only way to communicate with the production crew is through language. However, I was placed in a structure that has caused me relentless despair regarding the absolute condition of objectivity. After experiencing this limitation during 'Jump Cut', one of my solo exhibitions in 2008, I tried a more active type of work, one in which space planning and object realize the movie, as in storytelling. It may seem that my work is the result of a movie production process, although it is not a movie per say.

Koh: In all of your works, you use your own writing. The writing in your art pieces is of a very high quality. Why do you write?

Lim: I am neither great nor bad, but somewhere in-between. I have an inferiority complex when it comes to writing. However, when I feel frustrated, I start writing. I believe that literature is a form of art that is most humane, and I get strength to do something only after having failed. However, I merely give up because I know that I cannot write that well, even though I have the passion to write. That's why I did not write much. I am well aware that writing is a result of years of asceticism, just like the process of painting. And I am not the kind of person that has much time or perseverance...

Horn and Tail, Installation view at Gallery Plant, 2010

Koh: A few years ago, when the entire city of Seoul was preoccupied with its 'New Town' developments, the work New Town Ghost, based on the set of Yeongdeungpo, was regarded as very provocative. Was it a direct resistance to the thoughtless development?

Lim: I lived in Yeongdeungpo from 2005 until very recently. The surrounding Yeongdeungpo Station, which had been used as a hub during Korea's modernization period, was a place with a very unique identity; as such, it was portrayed as a setting for various pieces of literature, music and even movies. While living in Yeongdeungpo, I began questioning the model of Korean modernization and social development.

Yeongdeungpo was included as a part of the New Town project, but it was not developed immediately, so it is difficult for me to say that I was directly against it. The project represented merely one point during a long developmental period, but it represented my personal wish about what would happen and what would not happen to the area. You could say that I was venting against the ghosts of land supremacy and economic growth supremacy that lingered around the Yeongdeungpo development area.

New Town Ghost became an art form that adopted an instant format by borrowing from the code of subculture. As a writer, I am interested in inventing a heretical form that motivates the memory. We should remember the saying, "We are conquered, unless we remember." I think that artists should be careful not to regard a phenomenon as inevitable. If a universal rule is built by the bond of sympathy taught by the power of the state, creative art is a movement that does not agree with it. If you agree with it, there is no reason to raise a question or write/paint/compose.

Koh: Your way of questioning the aftereffects of rapid development in Seoul and other cities is aesthetically supported. It may seem that this can stem from ethical responsibility or from an outsider's 'exoticism.' What are your thoughts on this?

Lim: The ethical responsibility of art is an issue that draws attention from a number of artists. My stance on this is close to that of Jean Luc Godard's film "Le petit Soldat", who said, "Ethics is the aesthetics of the future." I am interested in the sentimental judgment phenomenon, which has moved from 'the good' in truth and beauty to 'the beautiful.' I believe that this is the same as looking into how our world holds disharmony together; it is because an action has to reorganize the sentiment about what cannot be seen, what cannot be heard and what cannot be spoken, as Jacques Ranciere had claimed.

In fact, aggressive urban development, as seen in Yeongdeungpo, is not an issue unique to South Korea. This kind of problem exists anywhere in the so-called 'globalized' world. I believe that I am against the political decision that sees an urban area or a part of nature as an object of economic development, through the eyes of the isolated and ignored. This 'Taking a Pause' is different from reasoning that either an outsider's exoticism or an insider's cultural superiority is somewhat distant from the fierce reality. I'm just wondering what contemporary art has to say about this social trend that is sweeping our generation with post-modernism, globalism, neo-liberalism, etc.

Koh: It seems that your work is not structured so as to focus on some single universal point. Do you think that the unique characteristics of your work may come from the aesthetical perspective of some locality?

Lim: I do not believe in the independent existence that can lead toward the aesthetics of globalization, or in corresponding to that locality. I am continuously opposed to some governing universality. Furthermore, I pursue what is open to possibility ‒ what can generate an independent stance. In this regard, I am interested in the individual and the regional lording.

During the process of compressed growth, it is possible to be self-contradictory. For instance, I consider negatively recognized expressions such as 'roughly' or 'quickly' as a surviving strategy or a trick, and I must admit that I benefited from those negative things, too.

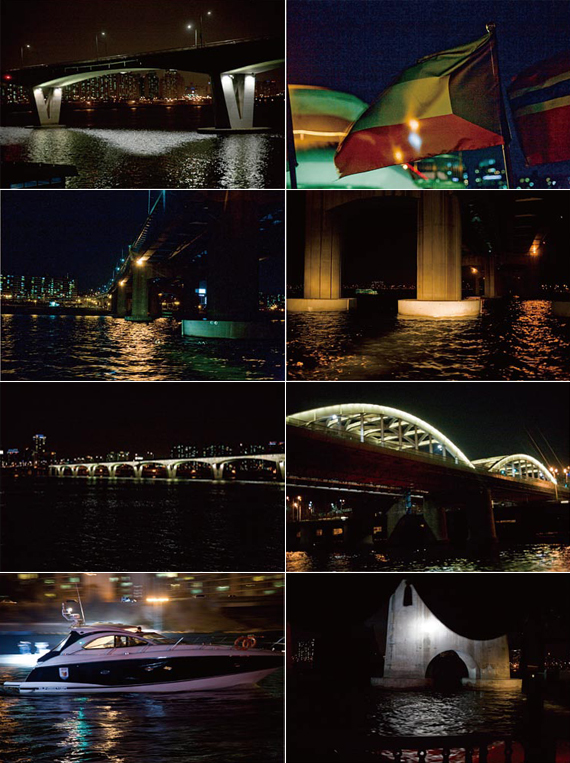

S.O.S. - Adoptive Dissensus, HD single channel video & sound projection, 46'13", Video documentation from performance, Seoul, Korea

2009

Koh: Your political opinions and stances remind us of the 'Minjoong Misool'(People's Art) that had survived during the dictatorship period.

Lim: 'Minjoong Misool' was great and heart-warming. The historical background and turbulent times made it possible. I was an outsider during those times, and I ended up studying abroad. However, my work is somewhat distant from the stances and ideas put forth by the people's art. Presently, I am living with a crisis different from what I felt during the dictatorship. It has become more dangerous and tricky, but it also exists as an enemy within, not on the outside. Thus, it may come alive only after I kill myself.

A crisis is near us when we cannot tell it clearly, when it is disguised. I thought about this on numerous occasions, when planning The Weight of Hands that I created as a new commission work for the Liverpool Biennale. It is like the thought that fighting against a ghost can only be done through a ritual of becoming a ghost? That means trying a new trail that sets the undivided regions and relations. In other words, only the priest who directs a production can give a command, knowing that the world we are living in is a Mise-en-Scene, or a reality that is often more fictitious than fiction. Otherwise, we will be lost not knowing a way out, being caught up by the razzle-dazzle of reality.

Koh: Is your work a self-reflection or the confession of an artist living in an age of reversed aesthetics?

Lim: I think that I am basically a pessimist. I am not sure if this is because I wanted to get over it with some manner of self-reflection and confession. The self-reflection and confession are ways to express an inseparable and paradoxical between a community and an individual. Preparing a performance called SOS-Adoptive Dissensus 2009, I reminded myself of the question, "What should I do to live in your life?"-which indicates the same kind of relationship. Because I am not completely separated from your reality, this confirms the feeling of solidarity that I cannot give up, although it may lead to some feeling of resentment and despair. Being self-reflective is the reason for the thoughts that had occurred to me as a subjective monologue to be persuasive; however, the drawing technique that I am trying to pursue is not expressed straightforward as a confession. Rather, it purses a more indirect and ironical drawing technique that penetrates and persuades people.

Too Early or Too Late Atelier, The 7th Hermes Korea Art Prize, Seoul, Installation view at Atelier Hermes, 2007

Koh: What do you want to express through your works in the future?

Lim: It seems that I have reached the educated art scene public, coming across as an educated artist in the past. No matter how difficult modern art is, I still believe that a connection between the public and me has taken place. I feel like I am satisfied with being positioned in an overlapped region. I have been dominated by the discourse of Western art and have worked in the same context. Although I tried to resist it on my own, it was only possible because I tacitly consented with the hegemony that the object had created. Now, I would like to start a new project, freeing myself from the hegemony that has overshadowed me for so long. It is my wish to work more truthfully. I would like to track the cultural entangling from the modernization period, something primitive and original, but neither unique nor common. I would like to tell a story beyond what we see, hear, know and believe to know. It seems that there is a place where the original spirit of the media resides. It is my belief that the nature of art should be set against the hegemony covering a wide range of genres, and the politics should also be the same.

New Town Ghost, Single channel sound & video projection, 10'45", 2005 ©Minouk LIM